It was a quiet Sunday evening. I was laying in my bed with my headphones on listening to my favorite Afro classics on shuffle when I first stumbled upon Tinariwen. I will never forget that moment, hearing the opening guitar riff for the first time. It was so raw, hypnotic and very bold. I was caught off guard and completely mesmerized, it was like a calling to the desert.

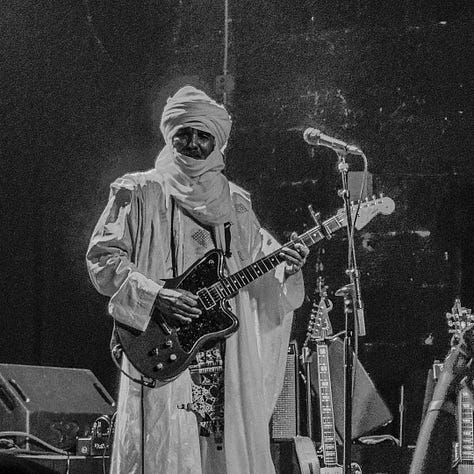

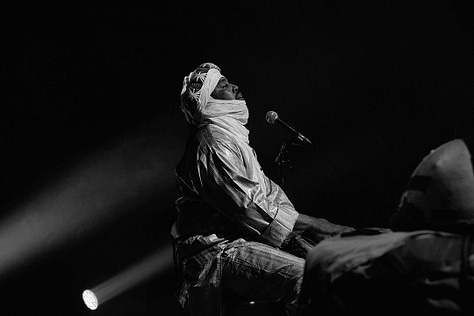

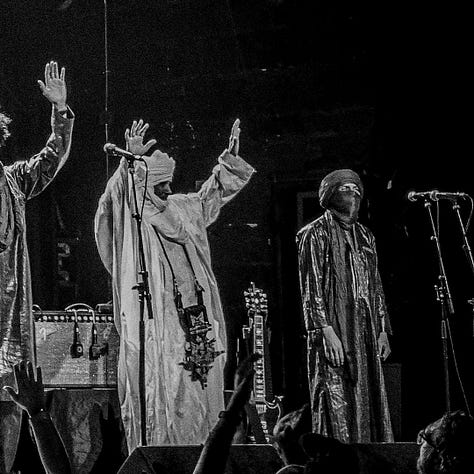

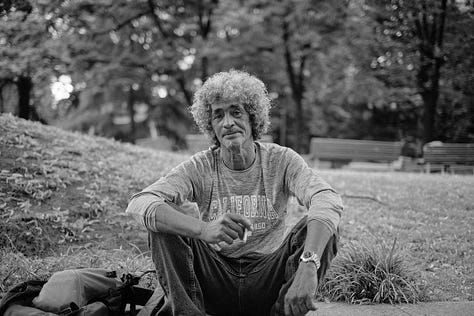

As the deep, haunting, and drunken vocals of Ibrahim filled the room, I couldn’t help but be captivated by the visuals that accompanied the sound. Ibrahim stood there, with his charmingly chaotic curly fro catching the light, while the rest of the band, their heads bejeweled with turbans, stood behind him, all gleaming with pride. I can still remember how beautifully they blended with the brown dunes of the desert behind them. You could tell they belonged there, like true sons of the desert. It was a moment of pure beauty and dignity, where the music, the people, and the landscape became one.

I began to feel a deep sense of longing, a strong connection to the desert. A place I’d never been but suddenly felt I understood. My favorite poet, the great Khalil Gibran often called music a “language of the spirits” and this came true for me in that moment. Although I understood not a single word of Tamashek, my soul grasped every word that was uttered by Ibrahim.

I knew I had fallen in love with the nomadic band when their faces and the echoes of their nostalgic voices could not stop lingering long after I had listened to their song. The music nerd in me knew deep down in my gut that this was not just music. It was beyond that. Tinariwen was a window into an unknown world rich with history, culture, poetry, and struggle. So, I began exploring their work and Tuareg heritage in general.

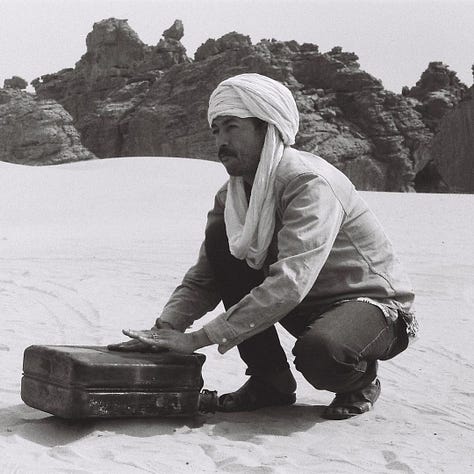

Tinariwen, in the Tamashek language literally means “The people of the Deserts” or “The Desert boys”. According to the band’s biography on their website, the story of the band begins when the founding father and lead singer Ibrahim met Hassane and the late Inteyeden while searching for employment in the Southern Algerian desert Oasis of Tamanrasset. Together they would perform at weddings and parties for members of the exiled Tuareg community. They performed songs that spoke directly to their fellow ishumar exiles - homesickness, longing, exile from their homeland.

The Tuareg are semi-nomadic herders and traders living in Northern Mali (what the Tuaregs call the state of “Azawad”) and the other side of its borders in Niger, Burkina Faso, Algeria, and Libya. They are descended from Berbers of North Africa and speak “Tamashek”, a Berber language. They practice Sunni Islam, and like many Africans, often incorporate traditional beliefs. They are thought to have left modern-day Libya in the seventh century CE as a result of pressure from Arab invaders.

The ishumar exile was a result of the oppression and hostility the Tuareg community endured especially under the Moussa Traoré regime in Mali. With the discrimination and worsening drought many had no choice but to abandon their nomadic lifestyle and move to cities, refugee camps, and into neighbouring countries. Many, like the founding fathers of Tinariwen, fled for Libya where they joined the Libyan guerilla training camps after an invitation was extended by Muammar Gaddafi to join his army with the hope of advancing their cause for autonomy or independence from the Malian government. To honor Gadaffi and the role he played in the rebellion of the Tuareg, they made a song Amalouna (“Our hope”) dedicated to him.

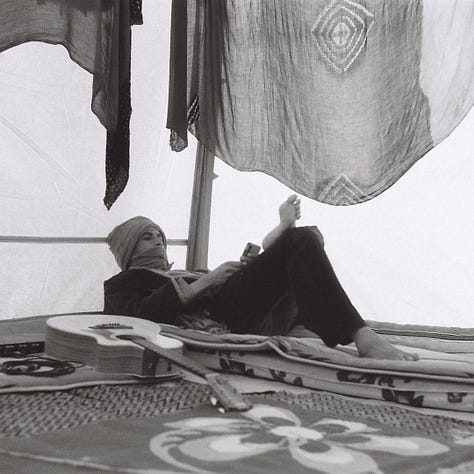

To deal with the pain of these many defeats i.e., poverty, homesickness, longing, war, etc., Tinariwen like many Tuaregs, turned to music and art to express their sorrow. There are stories about them entertaining their fellow fighters in a bush camp one night in eastern Mali. Some of my favorite songs include Koud Edhaz Emin (“Even if I seem to smile”), a song about having to put a brave face as they watch their people suffer from oppression. Tahalamot, a beautiful song about a woman so beautiful that the singer puts on his best robe and turban to pursue her and win her heart. And Ezlan (“Glory”), although I don’t know the meaning to this song, the first line Abdallah honors the imzad - a traditional instrument played by women.

What fascinates me about their music is its richness, a richness that encompasses culture, spirituality, history, courage, and an unbreakable connection to their homeland, Azawad. Their art is deeply rooted in Tuareg identity, and I feel that in every word and note. Not to mention the beauty of the Tamashek language that flows beautifully through their music. And when Tinariwen sings it becomes poetry, carrying the echoes of the desert and the timeless stories of its people, reminding the world of the beauty and complexity of a people often overlooked.

Another aspect that draws me to the band is their profound love and reverence for our continent. I think it’s evident not just in their music but in the way they present themselves to the rest of the world. Their reverence for tradition, their refusal to let the stories of their people and their homeland be forgotten. For me, they honor the continent by staying true to their roots, celebrating the riches of their culture while also paying tribute to the broader African experience. In their work I find a love letter to Africa – her beauty, resilience, and her indomitable spirit.

In the end, listening to Tinariwen has been a transformative experience for me. They not only offered me a glimpse into a world of beauty, poetry, resilience, and timeless wisdom, but they’ve also opened my eyes to the profound ways in which art can preserve history, connect us to our roots, and remind us of the love and respect we must have for our homeland and for each other. Their work is a beacon for anyone who seeks to understand the soul of Africa, and I will carry their music with me as a reminder of the beauty that arises when art and identity are woven together.

My dream is to one day witness them live, to feel the energy of their music wash over me in person, surrounded by the powerful rhythms that have come to define so much of my journey with them. Yet, it saddens me to think that time is passing, and they are growing older. The thought that they might retire before I get the chance to see them fills me with a sense of urgency. But even if that day never comes, their music will continue to inspire and guide me, a timeless reminder of the beauty and dignity of their art.

Song recommendations (with links):